***This is the first post in my series on The Paradoxes of Gentle Parenting.***

There are certain words we use to describe when our kids act up.

In English, we call it naughtiness, disobedience, misbehavior.

In Chinese, we use phrases like 淘气, 调皮,不听话.

The interesting thing about these words is that they are pretty much only used by adults when talking about children. We don’t use them to describe other adults behaving badly. We use them to express our disappointment and displeasure when children don’t comply with our adult expectations. Terms like “naughty” and “misbehaving” actually reveal how so much of our parenting is built on parental power and parental preference.

But what if there was no such thing as misbehavior?

That is exactly what Dr. Thomas Gordon, a clinical psychologist and founder of Gordon Training International, proposes.

“Children don’t misbehave, they simply behave to get their needs met.” – Dr. Thomas Gordon

Getting Needs Met

Everything our kids do they do to get a need met, whether it’s nourishment, nurturing, or someone to notice them.

The ways in which they attempt to get these needs met are not always appropriate or acceptable, however. Rather than concluding that the child as misbehaving (which would warrant a punishment/consequence), we can withhold judgment and instead consider what needs they might be trying to satisfy.

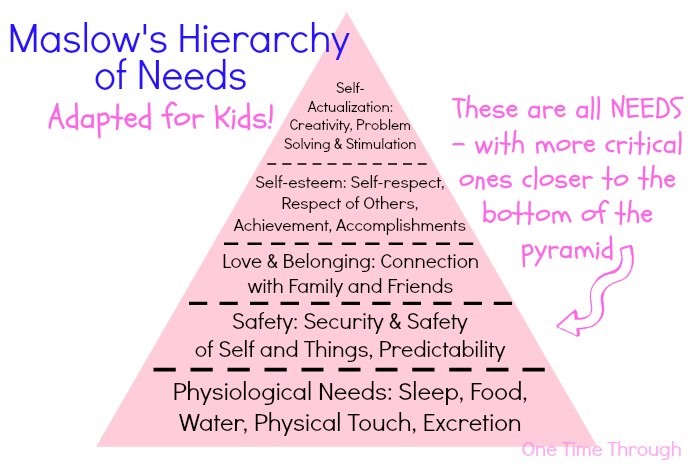

This infographic from One Time Through can help you identify your child’s needs:

The undesirable behavior may sometimes be resolved after a snack is eaten, a nap is taken, or a hug is given. But it may also be caused by a combination of unmet needs. Start from the bottom and address those basic needs before working your way up the pyramid. No worries if you don’t always read your child perfectly. It takes practice!

By framing all behaviors as attempts to get needs met instead of dividing behaviors into good and bad, we can begin to approach our kids with understanding and compassion instead of judgment and control. We can teach them to express themselves in ways that more effectively achieve their goals, solve their problems, and fulfill their needs.

When K.K. was in kindergarten, I attended a parent-teacher conference, expecting to hear how sweet and smart he was.

Instead, the teacher informed me that he had been hitting and biting the other kids.

What?! How could my adorable baby boy be the class bully? How could he make me lose face like that?!

At first, I contemplated what consequences I needed to enforce to nip the violence in the bud. But after some thought, I was able to consider what was probably driving his aggression:

He was stressed.

He was spending hours away from home when he was used to being by my side all day. He was in a Chinese-speaking environment when English was his first language. He probably didn’t always understand was going on, nor could he always effectively communicate his needs.

When I talked with K.K. later that evening, I asked him about how he felt and empathized with him. Then I gave him other tools to get his needs met. We practiced some Chinese phrases he could use, rehearsed different scenarios, and talked about how to ask a teacher for help. Instead of punishing him for his “misbehavior,” I was able to understand the reasons behind it and coach him with more effective and acceptable methods.

Instead of viewing our children through the eyes of what is convenient or comfortable for us as parents, let’s adjust our perspective and see them as growing individuals who are learning to understand and negotiate their own needs.

Let’s empathize with their hearts rather than simply evaluating them by their actions.

The crying that you once interpreted as disruptive is actually your baby’s cry for help.

The meltdown that you took to be your child’s stubbornness is a sign of overtiredness.

The backtalk that you once found offensive is really a need to be heard and understood.

Let’s stop branding our kids as bad, naughty, or misbehaving.

There are no such things as bad kids—only kids who are trying to get their needs met.

Let’s start helping them instead of punishing them for it.

Paradox #2: More Connecting, Less Correcting

4 Responses